Maria Cristina Didero in special and conversation with Oki Sato, the manager and the brain behind nendo

Maria Cristina Didero: How do you define your own space “in between”? I mean, what is the space between your professional life and your private life?

Oki Sato: There’s not much space in between my professional and private life – I spend my days constantly thinking about design. I’ve never really even thought of design as “work.” It’s just part of my everyday life, like breathing or sleeping. I think that the moment I begin to consider design to be work will mark my final day as a designer. If I really had to choose something, it would be the time I regularly spend relaxing with my pet dog, which is always with me at home and at the office. These brief moments are probably the only time that I turn off, so to speak. If you take the Japanese character for my name, Oki (?) and add a mark that looks like a comma (‘) to the corner, you get the Japanese character for “dog” (?). That’s exactly how it is – my dog provides a kind of punctuation to my life.

MCD: How would you describe the space in between objects? Something closer to emptiness, or a free ground in which to intervene?

OS: I think of it more as conceptual space rather than physical space. We each have these preconceived notions in our minds and as we trace the outlines of these things we notice that a fuzzy, ambiguous space exists between them. Preconceived notions are a fixed way of thinking, but the thought that exists in these spaces is infinitely flexible and fluid. I approach these areas with a playful intent, as if I were kneading and working clay.

MCD: How do you work in a team? Does collective work help you develop your ideas?

OS: Every single project at nendo has a single designer assigned to it. I work together with each of those designers, forming a series of twoperson teams to oversee and discuss each project as it progresses. While I am the one that comes up with the core ideas for each project, often unforeseeable situations will develop, or a project may move in a different direction or become much broader midway in. How those initial core ideas will develop and transform along the way is mostly unpredictable, and the final design will vary largely depending on the skills of the designer and how he or she handles these things. These element of uncertainty are one of the most exciting parts of design.

MCD: We all need a piece of happiness: your projects often encompass toy-like details, playful elements that generate positive feelings towards usually uninspiring objects such as, for example, storage units… What does happiness mean for Oki Sato or for nendo in general?

OS: I think there are both a good side and a bad side to everything in this world, and they exist in a relationship similar to that of light and shadow. Bringing the existence of an object’s “light” side to the attention is one of the missions of a designer. Doing so helps make the world a richer and more beautiful place. That’s why I try to incorporate a bit of humor into my designs and make them likeable.

MCD: What is the secret of your creativity? According to one saying, “creativity is, above all, the enemy of secrets.” Do you agree?OS: For me personally, there are no secrets to my creativity worth hiding, unfortunately. That said, I feel like it’s probably important to take an interest in the small details that other people don’t find interesting.

MCD: What is (or who is) your best ally in creativity?OS: Coming up with new ideas is not something that you do with a number of people – it’s a solitary undertaking. But at the same time, everyone and everything around you influences the process, so you could say that the people, the environment, and the information surrounding me all contribute to new ideas.

MCD: An Argentinean saying goes: “It’s said that to be a poet, you have to go to hell and back.” Assuming you are a poet of industrial design, did you ever go to hell? And if you did, could you describe it?

OS: In all of my time as a designer, never once have I taken the easy way out and been glad I did. Whenever faced with a choice between a “difficult” way and an “easy” way, I always make a point to choose the former, and much of what I have learned and experienced over the years is a result of doing so. I have to make up what I lack in exceptional talent with hard work. I not only continually attempt to push my own limits, but I also demand the same of other nendo designers, external collaborators, and even clients. I’m not really sure it would be appropriate to call that “hell,” though!

MCD: Do you think it is possible to find a balance between industry and poetry?

OS: Of course. I call it the balance between the right brain and the left brain. It’s no good to only be moved by intuition and feelings, or to only find joy in the rational, like concepts and specs. It’s the point at which the two come together that I’m always interested in.

MCD: Manias and passions make everyday life more difficult, but definitely render work more interesting, in the best cases Do you agree?

OS: I’d say that describes my own situation perfectly!

MCD: You are able to work incredibly well on different typologies of objects; it seems that nendo is embracing the world as a whole. Do you feel at ease in designing a piece of chocolate and a smart phone at the same time? And above all, do you have the same approach to both items?

OS: Regardless of what the object may be, the design process remains the same. Of course there will be a number of technical differences between designing a small piece of chocolate and a large interior space, but in both cases it will be living human beings that are coming into contact with the designs. The goal of eliciting an emotional reaction within those people doesn’t change in the slightest.

MCD: You seem to be completely seduced by your own job, and it is impressive how easily you carry on your projects (in the sense of maintaining quality while producing quantity, since you are very prolific). Somehow it seems that your designs come straight from your heart, combined with a solid knowledge of materials. Is there a direct bridge between instinct and experience?

OS: It’s true that I aim to produce designs that are uncontrived, candid reflections of what I feel whenever possible. I think that there are designs that are kind of like a stew in that they really develop flavor after being slowly boiled down over a long period of time, but for me personally my designs are more like sushi, in that I place a lot of importance on the freshness of the ideas. I try to work with deft hands, shaping the fish before the heat of my own body is transferred over to it. Unfortunately, there are times when experience gets in the way of intuition. With more experience, one becomes better at making predictions, and while this can reduce risk, I feel like it also brings with it the potential of the greatest risk of all, which is adopting a thought process that naturally avoids any kind of bold chancetaking. Figuring out how to find the right balance between experience and intuition within myself is probably one of the greatest issues that remains for me to resolve as moving forward.

MCD: Nothing ventured, nothing gained: what would be your most thought-provoking commission? What would be the most dangerous challenge you would be happy to face in design? Or is there an ultimate dream commission that you would like to face?

OS: I make it a point to not really think about those kinds of things, because the most dangerous or daring project for me would probably be something that I can’t even imagine anyway. The kinds of projects that I can imagine right now are far from what I would call dangerous.

MCD: Is there a moment, an occasion, a version of yourself that you like best? Meaning: which is your best version of yourself?

OS: Well, since I’m most likely to be productive when I’m coming up with ideas, you might say that’s my best version. I guess it depends on how you define best. (laugh)

MCD: It looks like your design started as a passion and became suddenly a dependence, a sort of addiction. You are a design-otaku (???), which I understand means a positive design addict. How can you be so creative and productive at the same time, and how do you manage to apply nendo’s way to different typologies of clients?

OS: I think that being a design-otaku is probably the reason that I can be creative and productive at the same time. When I look at things, I’m always thinking things like: “I wonder how this would turn out if such-and-such a designer worked on it,” or “I wonder what kind of finishing touches such-and-such a manufacturer would put on this?” Fantasizing about these kinds of things is almost like a hobby for me, and I think that as a result it contributes to my ability as a designer. I don’t find it difficult at all to maintain the nendo way when cooperating with our various clients. That’s because the “nendo way” doesn’t refer to any specific style or signature look, but rather is defined by the way we approach solving problems. It’s characterized by our perspective, in other words. Accordingly, we intentionally try to incorporate the client’s style into superficial elements as much as possible, and creating something that is a natural fit in the client’s catalogue is what we consider ideal. That said, it’s true that more and more clients have come to request the whitish, minimalistic elements that you can see in many of nendo’s designs. If that’s what the client wants then that’s fine, but I also feel like it’s moving away from the essence of creativity a bit. I think that it’s certainly possible to incorporate nendo’s way even if a design doesn’t happen to be whiteor is more complex.

MCD: You have two offices, one in Tokyo and one in Milan. Your team is composed of very young and dedicated people. It looks like nendo’s studio is a paradise for developing skills, and also a fantastic platform to start investigating the design world. It could represent the training school that all young designers would love to attend after completing their studies: who gave you the first chance to become who you are?

OS: I don’t know how the nendo organization differs from what people generally refer to as a design office. That’s because I’ve never worked at a design office, even as an intern or part-time. After graduating I began running my office through a lot of trial and error, and to this very day I don’t really know if I’m doing things the right way. For example, there was a period where I mimicked consulting companies and financial corporations by implementing the management practice of having each employee record the contents of their work in 30-minute segments, which would then be collected, analyzed, and discussed weekly. The goal was to reduce the stress being placed upon the employees, even if only slightly. By doing this, I could preemptively avoid overworking anyone and ensure that each person had the opportunity to take on new tasks, and I even experimented with calculating design fees based on working hours. But in the end I realized that all of this extra work was only causing even more stress for everyone at the office. So we got rid of that policy after only six months (laugh). It’s a continuous cycle of trial and error. I was never good at getting up in front of the class at school or giving lectures, but I keep a one-on-one dialog going with each of my designers and we work together to overcome any difficulties. This allows them to feel the weight of responsibility and gives me the chance to directly communicate a variety of things to them, I think. It’s the idea that growth as a designer is only possible through practice. What design schools – particularly those in Japan – do is kind of like trying to teach someone who has never seen water how to swim by explaining the action through words. It would be quickest to just throw them in the water (laugh). My job is to swim alongside them and pull them out of the water before they start to drown. It’s not uncommon for my designers to be headhunted by large corporations or well-known design offices after graduating and working at nendo for a few years, but I think that can be a good thing for them too. It’s almost as if nendo is turning into some kind of incubation chamber for the design industry in Japan. That’s not exactly what I envisioned our purpose to be… I’m just joking.

MCD: I believe you shy away from excess, you are modest in your use of colors and extravagancy, but always innovative and remarkable in the final proposal. What form of excess, if any, do you indulge in?

OS: When seeking a solution, it’s often so easy to add elements that I find it hard to do personally. Sometimes freedom actually feels restraining, and I think that the freedom offered by the process of addition is probably something that I haven’t really figured out how to handle. To me, design feels more like bonsai – trying to express myself with a single pair of scissors. The leaves and branches grow naturally, but by trimming them just the right amount you not only give the tree its form, but you help it continue to grow for hundreds of years. Perhaps my “excess” is actually expression resulting from removing as much as possible. When you really zoom in on the very limits of the boundaries between objects and take a good look, a whole different world starts to come into view and that world fascinates me.

MCD: Plato said: “Life without research is meaningless to live.” What are you currently researching?

OS: For me personally, every single component of my daily life is likely to end up as a topic of research. I don’t think that the act of researching something at a single point in time has much meaning. I think that research only becomes meaningful when it’s ongoing, continuing over an extended period of time. It’s only when you look at a phenomenon over time that you can make interesting discoveries, so it’s more like I am constantly observing what goes on around me.

MCD: I believe that inspiration comes from your soul, is elaborated by your mind, is transferred to paper with a pencil by your hand, and is then crafted by someone else. Have you ever made one of your pieces yourself, with your own hands?

OS: I almost never craft pieces with my own hands. I respect the skills of the workshop and those workers. They are manufacturing professionals, and I am a design professional, so I enjoy the process of working with them as equals, communicating with and bouncing ideas off of each other in order to create something.

MCD: As I see it, you are a storyteller, you are actually a writer of tangible images. When you sketch the first lines on paper, are you following nothing but your creative idea, or do you already take into consideration how the piece will then be produced? I mean, do you start from what technology already offers you, or would you rather struggle to find new ways to make your sketch producible?

OS: I make a sketch of the idea in its purest state, and the more abstract or poor that sketch is the better. A detailed sketch signifies the solidification of an idea, while a sketch that maintains a more fluid representation of an idea that lends itself to multiple interpretations leaves more room for further development afterwards. Designers occasionally fall prey to the seduction of gorgeous 3D rendering or sketches and lose sight of what is essential. It’s almost like some kind of drug. Or maybe I’m just making excuses for my terrible drawing skills.

MCD: Do you think design has a sociological relevance and should/could help people to live better?

OS: Of course. I’m not sure how much design can directly affect society or how immediate the effect may be, but I think it’s important to always seek to gradually improve things, no matter how slight this improvement it may be.MCD: What do you do in your free time?

OS: 1. Drink coffee. 2. Walk my dog. 3. Sleep as much as I can.

MCD: We all need somebody to take care of us. You take care of nendo, but who takes care of Oki?

OS: My pet dog.

MCD: “It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to,” as Jean-Luc Godard said. Could you comment on that?

OS: I agree that how you give form to your inspirations is important, but I have a feeling that, as a designer, where those inspirations come from and the process of how you attain them is just as important.

MCD: We all know where you come from; what I want to know is, where you want to take nendo in the near future?

OS: My hands are full with the projects we already have right now, so I don’t spend much time thinking about the future. I have faith that if I give my all to what I’m doing now, it will naturally lead to good things in the future. This has proven true so far.

MCD: Your objects could be considered sweet weapons of mass seduction. I mean, I personally know more than one person who bought them just because they could not resist: your objects are some sort of love blast – and this is not flattering. Within the design industry, everybody wants you, everybody likes to deal with you and your work. In one of your interviews, you said: “I just don’t want to be cool, I just want to be myself.” Did you ever have the experience of feeling so popular? Or being so cool – even if you do not like this word…

OS: Unfortunately, I can’t say I’ve ever considered myself to be popular or cool. I’ve had the honor of being featured in the media and receiving various awards, and while this makes me happy, the feeling of tension and the pressure to go on to do something worthy of those awards is even greater. Furthermore, receiving an award is made possible by a great number of sacrifices made not only by myself but also by the people around me, so to be honest it’s hard to let go and really get excited when considering what was given up in return. Now if it was something I didn’t have to work for like winning the lottery, you’d definitely see me celebrating!

MCD: What is your relationship with the international history of design? Do you consider anyone to be your master? Any masters for nendo?

OS: It’s a fact that architectural education is my foundation, but I would actually have to say that I consider the Japanese manga series Doraemon to be my “master.” In each story the main character ends up in a bind and each time some kind of gadget comes to his rescue. He’s not the smartest of the lot, but even so he manages to use the gadgets without any kind of user’s manual because they have an intuitive design, and on top of that they have a fun and likeable appearance. Also, the gadgets are never perfect, but that actually drives the development of the stories, in a way making it the optimal design. These designs that Doraemon pulls out of his pocket change with each episode – there’s no end to them.

MCD: Do you have any personal heroes in your life?

OS: My dad. He might not be the best father in the world, but he’s my one and only dad and he’s worthy of my respect.

MCD: What is the natural talent that you would like to be gifted with? Playing piano, dancing, etc.?

OS: The ability to recognize which clients aren’t a good fit for me. It’s something that took far too long to learn how to do (laugh).MCD: Well, this is already a talent!

MCD: It looks like your favorite occupation is sketching. Can you mention another one?

OS: Sketching would be my second favorite. My favorite would have to be observing things.

MCD: You said you are addicted to design and that “I enjoy what I am doing”: what are the others things you enjoy the most?

OS: That’s it, really. I find comfort in doing the same things over and over. Every day I walk down the same road, drink the same coffee in the same chair at the same café, and wear the same outfit – a white shirt, black pants, black underwear and socks. This gives me the most peace of mind. My projects are full of constant change, so I don’t feel the need to seek out change elsewhere.

MCD: You said: “if you do not see the solution, the story behind an object, I do not carry on the conversation.” Fair enough: so when do you have the feeling that the conversation with a client does not go anywhere? Is there a specific sign that your radar is able to capture?

OS: If a client comes looking for something and I can provide that something, then I happily do so. When the client isn’t sure what it is they are looking for, then we come together and search for what that thing may be. When a client is adamant about chasing something that just isn’t possible, I inform them of that reality. If they then continue to demand that same thing, then I politely end the relationship there.

MCD: You said once that a good design can be described on the telephone and understood easily by everyone. Is design really about communication?

OS: I’m always searching for the kinds of ideas that have the power to move people regardless of form. Those are the ideas that can go beyond culture and transcend space and time to touch a greater number of people. Creating an object that lacks an idea at its core is not design. That is nothing but an empty shell.

MCD: According to your position, the object has to tell a story, it has to communicate emotions. Which of the products you have designed tell us the most interesting or relevant story?

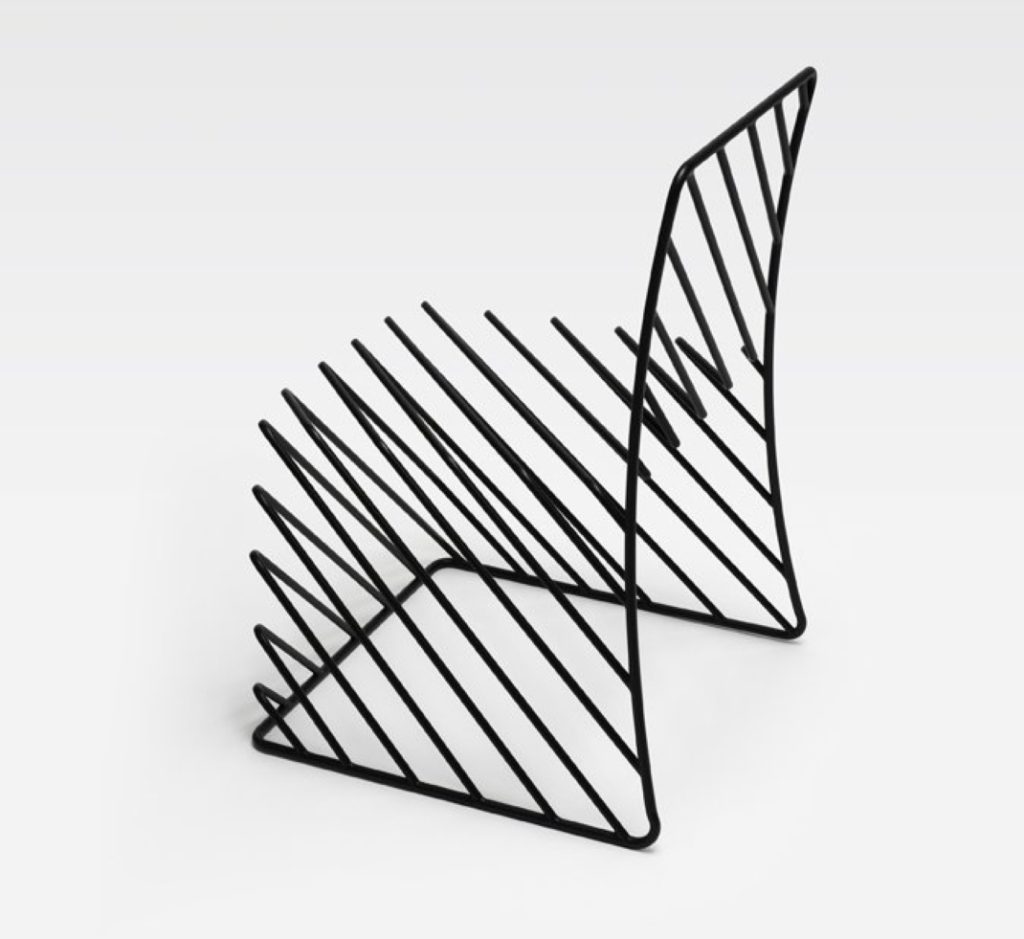

OS: Every design has its own unique story, and choosing any one of those as the best is impossible for me. That said, an example might be the “thin black lines” chair. There was a piece of paper with a sketch of some random chair on it, and an eraser just happened to be sitting on top of it. All of a sudden it appeared to me as if the eraser were actually sitting on the sketched chair, and thus the design was born – a chair that resembles a flat, two-dimensional sketch.

MCD: You said that, “without dreaming there is no innovation.” Emotions and technology go well together in your work. What is your approach to technology and craftsmanship? And to what degree do emotions make a difference in a project?

OS: Emotional elements will always play a central role in my work. From there it’s a matter of choosing the technologies, materials, and traditional craftsmanship that is most fitting for those emotional elements, almost like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. When the pieces fit together perfectly, that’s when innovation occurs. That said, on vary rare occasions do the materials themselves have intrinsic emotional value, in which case I will pay close attention to the materials to bring out that value. The “cabbage chair” project might fall into that category.

MCD: As you put it, “The word function contains the word fun.” Is fun fundamental for you? What are the pillars of Oki’s approach to design?

OS: One of the pitfalls of minimalistic, simple designs is that they can sometimes give off a rigid and cold impression, since the functionality is right there, exposed before your eyes. I think that by sprinkling on emotions like joy and surprise as if they were seasonings, you can create an intimate sense of connection between people and an object or space.

MCD: Difference creates ideas. Do you agree? For example, you and Luca Nichetto are very different, but your collaboration had pretty interesting results in terms of the final product.

OS: Differences can be fascinating, but there must be a sense of respect and understanding underlying them. Otherwise they can be a very dangerous thing.

MCD: Design is about finding new perspectives concerning ordinary things. But sometimes, the ordinary is also interesting. What is ordinary for you? And what is extraordinary?

OS: I don’t think that there is such a thing as an ordinary thing in this world. If you look at something and it appears ordinary to you, I think that it’s really just your way of perceiving that thing that is ordinary.