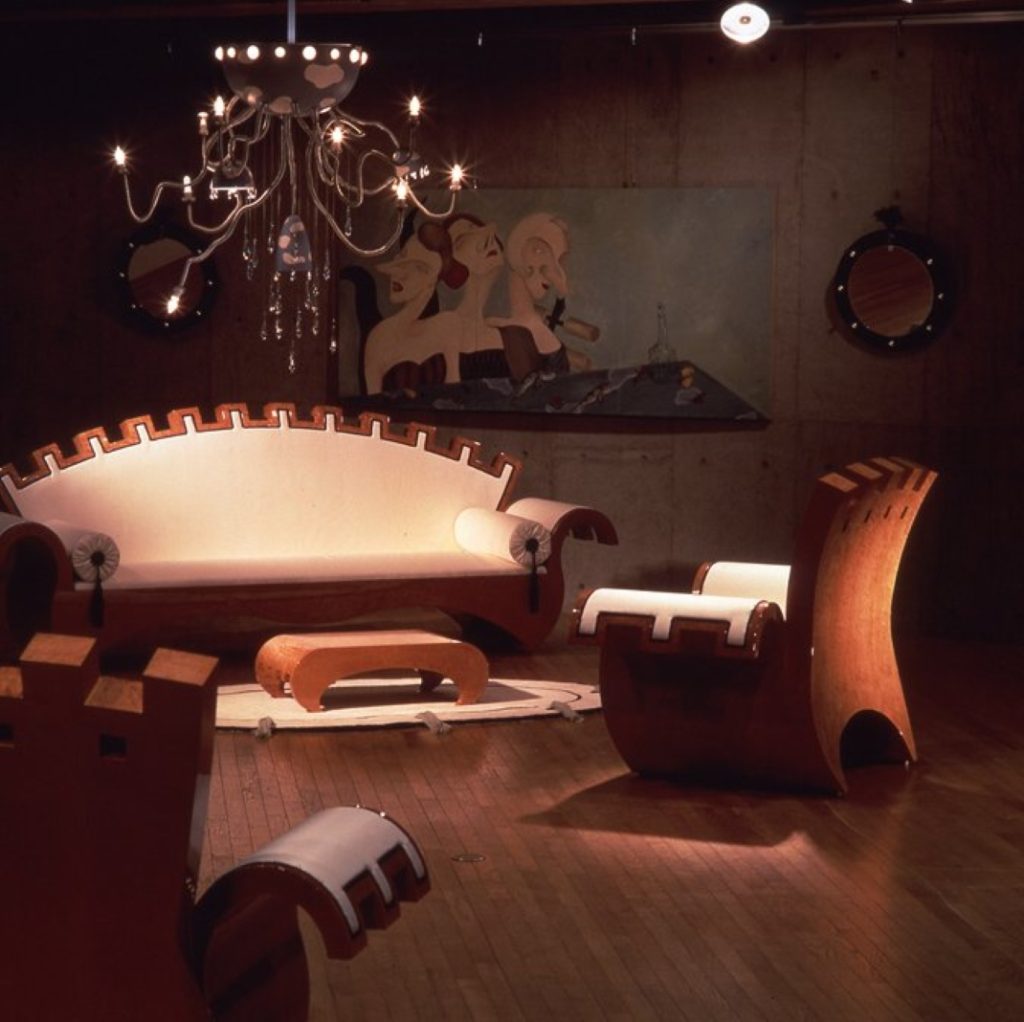

From your first encounter with Hironen’s furniture, you stop thinking about furniture. You begin to think about strange libidinal creatures, that compel you into awe.

From your first encounter with Hironen’s furniture, you stop thinking about furniture. You begin to think about strange libidinal creatures, that compel you into awe. The shock effect dictates very instinctual viewing, which has little to do with the “objectness” of the objects but rather with their mental-sexual energy. They symbolize people in the world of Hironen an armchair, sofa or lamp possess a body , desires, sensing organs-nose, eyes, mouth, skin.

A body that reverberates with its own desires, erotic fantasies and affections. Affections so perfect that you are tempted to believe that they are the true representatives of your secret desires. They will dwell with you and you will dwell in them, yet they will never have a full authentic existence – merely a representation of a literary existence, symbolic and fantastic, a fairy tale existence.

The body of the armchair, sofa or lamp insists on being both presence and hallucination. Something in this “body” – an artificial leg, a hump adorned with a rose, some dimple up on the buttock, a nose that grows and elongates and threatens to fondle your back with desire, a train that offers itself as a carpet for your revered feet – something grabs at your feelings. Perhaps like the way a beautiful body with a slight deformation or “aesthetic defect” can wrap your desires around it.

There’s something about that body – of the armchair, sofa or lamp – that really touches your heart. What is that something? It’s the heart of the thing itself. The heart of the thing touches your heart. Not every object has a “body”, but very rarely does an object have a heart and libido as well as a body. Hironen’s objects have the developed body, heart and libido of a swaggering peacock. If anyone thinks that a swaggering peacock can’t be touching, he should try to mind the deluded characters that walk around like court members with a splendid past in Nisim Aloni’s surrealistic plays. But maybe it would be better to imagine a peacock after all. A peacock with tail feathers that do not succeed in weaving perfect eyes, and yet the same peacock never tires of extravagant courtship gestures. He spreads his tail according to all the rules of etiquette; the fan will be perfect even if the feathers’ design is flawed.Think of another phenomenon of nature: Think of Hanoch Levin-type existence, of the grotesque characters long situated on mythical heights. Of their gluttonous, ugly, hungry, despicable and cruel existence. Of their stubborn determination to protect their image in each other’s eyes, to defend against all odds the tail of their dream to be who they never were and will never be; to act piggishly at everybody else’s expense so long as they’re left to live out their pretty illusions, to significantly live this pointless life, partially of fully, as long as it’s to the final breath. And think of the execution, of the cruel level of accuracy in this redundant kind of existence; think how they compulsively progress through their world, of their highly designed style – then you’ll see that tail fan spread itself out in its full glory and draw incredulity from you. Incredulity about the ability of the ridiculous to be sublime, the grotesque to be beautiful, the absurd to be possible.Ronen Levin: “The willingness to be ludicrous in order to win love is a point that radiates permanent pain. The actual attempt to be an artist seems heartbreaking and pathetic no matter which art we are talking about. After all, even Joseph Beuys was a court jester”.Hironen, brand name and design studio, established about six years ago in Tokyo by the Israeli Ronen Levin and the Japanese Hiroyoki Okawa. Fusing two biographies which had flourished on different cultural backgrounds gave birth to a fascinating Metissage of modernist aesthetic values, which have nothing obviously in common either with Japanese or Israeli aesthetic traditions or with the extremities of Modernism. The things they create are meant first and foremost to inspire sensual pleasure and to emphasize skill and good taste and not arid intellectualism.

They began their joint activity out of artistic freedom, strangers to no culture or aesthetic tradition. If they felt any obligation, it was to “take flight” to wherever their imagination carries them, so long as they remain faithful to an inner code of taste, beauty and identity. After all “design is identity”, as suggested by an international design exhibition currently at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark.Levin and Okawa are obsessive about their obsession. They push their meticulous insistence on appearance, control and style to the very limit. This obsession does not contradict the freedom that Hironen embraced in creating works of art that combine forms, viewpoints, attitudes and dialectic concept reflecting their attitude to life: pieces that do not shrink from appearing glamorous and ridiculous, beautiful and ugly, solid and unstable, whole and defective, flowing and harmonious yet stiff and fixated. Sofas that are not ashamed, on the one hand, to wiggle with shameless abandon and, on the other hand, to act as self-righteously as a church confessional. Impertinent armchairs that decorate themselves with roses and stars and bright cloths and colours, and sombre chairs that yield to the material, and even worship it.

Some of their pieces formulate fluent gestures toward the virtuosity and sparkle of the Rococo, which celebrated the beauty of life, while others pay dues to modernist sources of inspiration, like Bauhaus and Minimalism, which reflected the transition to an industrial society and the result of that transition. They also have narcissistic pieces with a disquieting erotic presence, which brings to mind existential experience, decadent style, surrealistic contexts and murky theories about the relations between eroticism and death, complex relation that are often violent, as embodied in the works of Georges Bataille, Freud, Sade, Bauldelaire, Oscar Wilde amongst others. Nigel Coats, founder of the “Narrative Architecture” stream, said of Hironen’s work that it is not design, but “criticism of design”.

Each of their pieces is one of a kind, but when you try to think of everything that Hironen created till today, you get a rather wild genetic dynasty. A dynasty in which all their creations comprise a kind of family of step-children, with weak blood ties. Hironen’s “heroes” are not satisfied with being beautiful. They proclaim their beauty; they confer their charms; they bestow their gallant gestures. But when one tries to imagine who could actually live with them, it’s the characters from Hanoch Levin’s plays who naturally come to mind. For example, the characters from “Everyone Wants to Live”: Po tzna, the rural baron; Potznavocha, his wife; Potznasmarks, their two children; Bamba; Titi; Softof Rachmaninov; Golgolevitz; the crying girl; the hunchback; the amputee; the servants; the guests at the ball; the wandering actor.

Each of these characters is a kind of marionette of perfection and style. So are the Hironen paintings and furniture. They dictate a way of sitting and behavior and seemingly aristocratic gestures, but actually it’s a caricature of aristocratic gestures. Characters from Hanoch Levin plays could live in a house with this kind of furniture. But Potzna – the baron who agonizes because he is served Hungarian salami with mustard that is not Dijon – is also a caricature of us, because Hanoch Levin formulated a lexicon of humanity. An inarticulate, longing humanity, always lacking something, which came blemished into the world, without anything metaphysical or transcendental about it. Therefore it is human. Like the furniture, which because of its perfection and glorious loneliness, mocks those who use it, just as the desire to create beauty emphasizes a lack of beauty.

Hironen’s charming “creatures”, heterogeneous in style, radiate brilliance and oddity, estrangement and disconnection. Estrangement from each other, and also in relation to themselves and their locale. Wherever they position themselves, somehow they are uncomfortable. As if they were members of a club, ex-territorial, whose membership condition are existential estrangement and strangeness. These “creatures” touch the heart because they are “deviants” who can’t find their place, yet fastidiously appear at their best, as though they were Knights of Style – perhaps even in Count Potzna’s court.

Ronen Levin: “I think that my objects look best when they feel like outsiders… it might be connected to a memory that I have. After my grandmother died, I burrowed through her estate and found a photograph of her, taken shortly after they arrived in Palestine from Poland, via Belgium. In the photograph she is standing in a tailored suit, with gloves and a hat and a net veil… in sand dunes. Tasseled in the sand dunes. Absolutely chic, absolutely wonderful and absolutely heartbreaking. I think that in everything I will ever do, I will always be aiming for the same impact that photograph had on me. That’s how my Utz-Li Gutz-Li armchair also feels: tasseled and dressed up in red velvet, with a long train, embroidered with gold stars, sitting in some emaciated space. Like an eccentric exiled countess”.

Most of the Hironen objects are an incarnation of painted images. It is the paintings-which impart complete congruence and are an inseparable part of every setting that Hironen produces – that remind the viewer the most that the world in question is designed. In other words, the paintings are more “designed” than the designed objects, while the objects are more picturesque than the paintings. The paintings complete the mise en scene. If it is not clear how one should behave in the company of the objects, the paintings come along and function as stage directions. How to dress near them, how to put on makeup and arrange one’s hair, what to eat, how to hold the porcelain cup, in what position to hold one’s head, how high to lift one’s nose; how to relate to one another, what is the range of permitted gestures and mannerisms. The etiquette of being in their presence.

It is in the paintings that one finds the most acute expression of existential pain, which is linked to the longing for the beautiful and with a feeling of abnormality. Always the same women, forever sitting round a table. Always huge noses, like Cyrano de Bergerac. What looks like a relaxed, stylized tea-party induces nervousness and unease. Or, perhaps, as Oscar Wilde said: “No object is so ugly that, under certain conditions of light and shades, or proximity to other things, it will not look beautiful; no object is so beautiful that, under certain conditions, it will not look ugly. I believe that in every twenty-four hours what is beautiful looks ugly, and what is ugly looks beautiful, once.” (Oscar Wilde, Lecture to Art Students, 7 Arts, Falcon’s Wing Press, Colorado, 1955).

Ronen Levin burrows through his painted gallery of deviants again and again, obsessively, like someone trying to formulate a human confession about a nonsensical world, engaged in frivolities. A world which feels kind of empty, but exists in sexiness and “style”. Ronen lives with the feeling that he actually sits and chatters at these tea parties, trying to make some kind of existential sense from them, captivated by them, as though their nonsense actually imparts a reason to exist, while at the same time he undermines them with self-irony and ridicule.Levin: “it seems to me so painful to be a part of such a world, a fraternity of people united on the basis of one strange, dominated details: their large nose, it’s an oddity that tyrannizes – the nose decides for you. It’s a fatalistic feeling, like my elegant grandmother in the dunes. Then I try to examine what group I “belong to”: Jew, Israeli, stranger in Tokyo, artist. Each of these affiliation groups seems to me like a club of people who are ruled by their oddities, who sit together and hold melancholy tea parties”.Hiroyoki Okawa: “we don’t need any more cold, soulless high-tech objects. On the backdrop of the post-apocalyptic and deconstructivist visions that have filled the art world in the past decade, I would actually like to create amusing, good hearted objects. I feel an almost moral obligation to come out with something that will act as a remedy for depression. The fact that Ronen speaks of melancholy, that’s another matter. Melancholy is not necessarily an expression of existential despair. It can still be a lyrical experience, which can also cause pleasant nostalgic remembering. These are sensations that I feel obligated to summon out of the oblivion after years of denying and rejecting them. Yet it’s still important to maintain the thin line between kitschy sentimentality and the refined touching of spiritual – mental – emotional focal points”.Hiro, though a descended of a family of Japanese Buddhist priests from the Shikenji sect, and though he grew up in a temple and was raised on traditional Japanese values and aesthetics, proclaims his desire to create things which are more “wagamama” (in Japanese: egocentric, individualistic, ignoring the general harmony. Needless to say that while in the West individualism is considered a positive value, this is not so in Japan) and fewer things that declare of themselves as being “social-cosmic”. Things that are derived from a private place and sensibility, yet radiate communicability, kindness, compassion and good nature. These are qualities that will cause anyone to stop by their side, even if the objects are not exactly to their taste. Hiro speaks of the object’s essential quality as a conversation piece.

Like Ronen, Hiro also expresses his affiliation with objects that bear qualities of melancholy, compassion and longing. One of his childhood memories, which in his opinion illustrates this tendency, takes him back to age four, when his grandfather carried him on his shoulders in the temple garden and showed him the last persimmon on a tree. ‘It’s going to fall,” his grandfather told him, “this is the autumn sadness. Do you feel it?”

Hironen’s language of form relies on a brilliant professional aesthetic ritual and on a unique accent and personal grammar. Ideologically, there is no doubt that they are not among the designers who channel their creative energies in the direction of “democratic design” design whose production, effectiveness, indispensability and price are suitable for everyone. Social ideas that were born less than one hundred years ago and championed “beauty for everyone”, “tables and chairs for every worker” and “the ideal house for the proletariat” – objectives that tried to mediate values of simple, inexpensive design – never really achieved their goal. Despite the last decade, which was characterized by a “design boom”, it is still too soon to speak of a developed aesthetic consciousness in the general public.

“Popularity”, said Oscar Wilde at the end of the last century, “is the crown of laurel which the world puts on bad art. Whatever is popular is wrong.”(ibid).

Toward the end of the millennium, on a background of the medley of styles gathering under post-industrail hegemony, one can view their work as the final stage in a culture of taste. A culture in which they would like to believe that the principle of beauty never actually ended its period of tenure, that their style is perhaps the last universal style in which the “beautiful” and the “artistic” are once again synonymous. In this matter, there is no doubt that Hiro and Ronen would embrace sampling of Oscar Wilde’s words: “…all pictures that do not immediately give you such artistic joy as to make you say ‘How beautiful!’ are bad pictures.” (ibid).

And yet, contrary to what mistakenly might be deduced from their statement, it would not be advisable to ignore the social-cultural aspects of their work: First, their ambition to promote various craft skills and practices in opposition to industrial production processes. More than that: their needs to talk of a private identity that proclaims itself as “otherness”; the attempt to point out man’s condition in industrial society, a mobile society that detaches people from their regional context; a society in which people find themselves shifted from their natural place and turned into “deviants”, doomed to wandering and repeated detachments, like one who carries his own air roots with him wherever he goes. What could be more relevant and neo-humanist than the desire to mediate-particularly in the most mediated and media-covered world – their solitudes.

Hironen’s armchairs, sofas, tables, chests, lamps, paintings, tableware, objects d’art and jewelry express a powerful fusion of “unmeasured” fantastic forms with a lucid concept. They arrive at their point of departure – and, after all, their point of departure is always lucid – from a place that aims to wrestle with new ideas, and not from a place that strives to compromise their creativity. Usually they think about the form and how it affects the space. Hironen often design their objects much like a choreographer designs a dancer, i.e. they try to design not only the things themselves, but also our experience of them in space. According to their aesthetic concept, when an object is being designed, movement and space play a vital role and are as essential and substantial as the line, shape, material and function. Movement and space play the role of shadow in a painting, shadow that helps define the object’s material and outline.

The exhibition, which will be situated in some ten rooms in the “Colonnade House”, strives to mediate the natural tension that forms between an old structure designated for conservation – including the poetics in its stained peeling walls that hide or expose a rich stylized “European” past, and including what we have grown used to calling the Tel Avivian arte povera, which is actually all-Israeli-and the pomp and splendor radiating from Hironen’s objects. The objects’ migration from Tokyo, (the very heart of culture which has been a design empire and a focus of aesthetic inspiration for Western artists from the end of the last century), to the area where the first commercial center of Tel Aviv developed, (a city which never held a dialogue with design), will impart to the exhibition an effect symptomatic of the “Israeli experience”. An Israeli experience in the sense of “artificial splendor”, forever in relation to someplace else, as Hironen’s eclectic style expresses a substantial relationship with and a longing for other places, other periods, other courts.In a certain sense Hironen’s objects will fuse with one of their creators’ biographies and will expend their rhetoric when they will be placed on the sand bedding in the “Colonnade House”. The sand will partially cover the ornamental tiles that survived along with the original building. Several objects will be detached from the whole set and will be situated “alone” in the space – “tasseled in the sand”. Because of the objects’ individualistic personalities and their disparate styles, by placing them together the overall impression created may be one of caprice, but even if it is caprice, it is well argued and faithful to the “story”, whatever the story may be. The “caprice” will never go wild in the sense of insisting on brittle fine cloth I places that the object allows for tougher, more enduring cloth. Even when the object appears to be minimalist or completely modern (Speedo, for example), this doesn’t mean that its shape derives from its function, but rather from the language which serves the story that they wish to relate at that particular moment.

When they invent a wooden armchair which is nothing but a large wooden cube with a smaller wooden cube issuing from its center – a kind of baby block emerging from the large block’s abdomen in order to serve as a foot stool – they will be the first to admit that this armchair is not the most comfortable one in the world. They add, however, that it was never intended for continuous sitting in the corner of a room, bathing in the light of a floor lamp near the fireplace, and that generally speaking it wasn’t made to any kind of order. It was invested to tell a modernist legend about a big cube that gave birth to a little cube, and how each one then had a precise role in life. Usually, though, the objects are far more complicated to produce, so complicated that it’s not enough to find the skilled craftsmen capable of dealing with the sketch and model. Often Ronen and Hiro are required to be present in person, to stand at the side of the craftsman who is slowly growing more entangled and frustrated before their very eyes, like someone making mistakes in deciphering a multi-level painting and not necessarily a real object having volume, materials and standard measurements. There are still things waiting to be embodied in material, since the craftsman who can deal with them has yet to be found. In Israel it’s usually a whole song and dance, but even in Japan it is not so simple. Ronen and Hiro wandered there from one craftsman to another with their model of For Alfred Loos with Love and Squalor (two armchair and a sofa that look like a fortress or tower on the top of an enchanted castle), and were turned down flat everywhere. Finally the savior was found in the shape of a carpenter who specializes in building “Butsu-Dan”, the small ornamented cabinet-alter found in Japanese homes, on which urns with the ashes of deceased family members and offerings for the gods are placed. The carpenter lives in Fukuoka, an hour and a half flight from Tokyo. The For Alfred Loos with Love and Squalor set is made of maple of the “bird’s eye” type, wood that is especially expensive because of its rarity. The craftsman was required to band the wood in an arch both vertically and horizontally at the same time. He worked on it day and night without sleeping, and in the end he couldn’t resist signed his name and the date under the upholstery. The cushions and upholstery are made of real ivory colored silk-satin, cloth that they could find only in bridal shops. The set, by the way, was sold for seventy-five thousand dollars. But the most complicated to make was Rumpelstiltskin. The techniques involved are those of a sculptor, not a carpenter. The material, polyurethane foam, had to be literally carved and then dressed in a “dress” which also complicated to sew because of its organic shape. The cloth had to be embroidered in such a way that the roses or stars would “fall” in exactly the right place, without any creases forming.

The Biedermeier chairs as well didn’t make life easy for anyone: The back leg “pierces” the upholstery like a sword, while the front legs are made of another material, metal, and look like artificial legs that screw on. The same goes for the Love Seat: Two massive pieces of wood, like cabinets, their stability depended on each other since each unit has only two legs instead of four; or the lamp And Don’t Forget the lapdog, an object which required a genius glass-blower to reach the exact shade, degree of thickness and the particular shape of stalactites.

It is very difficult to translate Hironen’s free forms onto paper. Most of their pieces look different when you look at them from different angles. No plan or line develops in a logical sequence; you cannot deduce from the front how the bace will appear. This means that the illustration of the object in a drawing may require many dozens of drawing, done from every possible angle.So why the title “For Alfred Loos with Love and Squalor”? Who is Alfred Loos and why is he relevant to our period?Alfred Loos was one of the forerunners of the modernist movement in architecture. His acerbic articles of criticism often berated the exaggerated ornamentation that characterized Vienna at the end of the 19th century and the forced attempts to beautify the new reality that followed industrialization and mass migration from the countryside. Reading it today, his criticism of modern culture reads like criticism of our last decade’s understanding of unrestrained, eclectic and quotational historicist Postmodernism.Loos’s paradoxical critical arrows did not pass over the leading artists of his day, who were considered innovators and belonged to the Art Nouveau school (an overly decorative trend that tended to adopt “original” objects and to take exception to what was considered a “period” style; it was characterized and inspired by plants, flames, waves and the stylized flowing hair of women figures), and to the Secession movement, a name adopted by various groups of German and Austrian artists who rebelled against the salon system of the last decade of the previous century, and offered innovations that found expression among other things, in blurring the borders between “high” and “low” art. The president of the Secession movement in Vienna was Gustav Klimt.

Loos’s classical tendency towards the cube-like form and his stormy exhortations about the need for restraint, functionalism and comfort brought forth Purism, anticipating the abstraction, straight lines and division of inner spaces of De Stijl’s levels, and in effect dictated the main principles of the International Style in architecture. Loos, however, was not happy with the simplistic manner in which his thoughts were adopted, since he did want to reflect the prosaic life-style of his time in building and design, without being drawn to folk “authenticity” and artificiality, yet without relying on decadent classicism. As he said: “Everything that the Italian Renaissance created in the shape of richly ornate mansions, was plundered and copied in order to invent for Their Highness the Common People a new Vienna, which only people whose rank allows them to own an entire palace from celler to chimney can live in…”(Die Potemkiinsche Stadt, satirical article from 1898).

According to Loos, expression and ornament must evolve from the material itself, without waste of manpower or materials and taking into account the circumstances and the surroundings. “Rich materials and excellent work must be interpreted not only as a compensation for lack of any ornament, but as far surpassing it in their splendor.” In other words, it is permitted to bend the wood in order to draw rich expression out of it, but there is no reason to add carving or etchings. An urban architect is allowed to build a bourgeois villa in a neighborhood of bourgeois villas, but he must not presume to plant the aristocratic culture of Western Classicism in an urban-bourgeoisie environment, since this too will look like a kind of hormonal imbalance.

In 1908 Loos published an article, whose title “Ornament and Crime” gained immortal life. In this article he deepens his dispute with the hazy self-conscious fantasies of the Secession artists and broadens his moral and aesthetic criticism. “Low Art”, i.e. authentic treasures, he leaves only to simple craftsmen, artisans who cannot enjoy the lofty achievements of the bourgeoisie and for whom producing ornaments is the ultimate climax of their aesthetics talents. They – the cobblers, carpenters and tailors – are permitted poor things, because they have no culture. Perhaps like a typical conservation businessman, Loos prefers that the pair of shoes in which he marches to the opera will be efficient, ordinary and mainly unassuming, however if their non-simple lines express the cobbler’s best aesthetic skills, he can accept that. In such a case, he claims, the ornament is justified.”After a day’s trouble and pain, we go to hear Beethoven or Wagner. My cobbler cannot do that. I must not rob him of his pleasures as I have nothing else to replace them with. But he who goes to listen to the Ninth Symphony and who then sits down to draw up a wallpaper pattern, is either a rogue or a degenerate.” (Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime, article from 1908 appearing in Arts Council 1985 catalogue).”The urge to ornament one’s face, and everything within one’s reach is the origin of fine art”, Loos writes in the same article and with the same pathological tone. “… All arts is erotic… The first work of art, the first artistic action of the first artist daubing on the wall, was in order to rid himself of his natural excesses… (but) Man had progressed enough for ornament to no longer produce erotic sensations in him… what is natural to the Papuan and the child is a symptom of degeneration in the modern man… I said, ‘weep not. Behold! What makes our period so important is that it is incapable of producing new ornament. He have outgrown ornament, we have struggled through to a state without ornament. Behold, the time is at hand, fulfillment awaits us. Soon the streets of the cities will glow like white walls! Like Zion, the Holy City, the capital of heaven. It is then that fulfillment will have come’. (ibid).

Hironen, then, has an ambivalent attitude towards the like that Loos forged between ornament and crime. From their point of view, perhaps like the “degenerate” concept of the Secession artists, the self-aware ornament has an important psychological-erotic role that hasn’t changed from the beginning of the history of art. Which ornament? That already is a question of taste and stylistic tendencies. After all, Loos himself accepted a certain type of ornament (mostly archeological). In the spaces that he designed he rebelled against logical proportion. The houses that he planned did not necessarily induce an atmosphere of comfort and efficiency. The villa that he built for Josephine Baker in 1928, for example, is a paragon of ostentation and an object of admiration for Ronen Levin and Hiro Okawa. The same is true of his “Elephant’s Trunk” coffee table from 1900, made of mahogany with brass legs and borders, a table that was a great favorite of Loos’s and which he often used in apartments that he designed.Ronen and Hiro: “if there are details that are required in order to tell your ‘tale’, they should not be treated as ornament but as essential, vital forms. We have no fear of empty surface, sometimes they are absolutely necessary to us; it’s just that sometimes there is a need for embroidered roses to complete the particular story. Ironically the artistic language that speaks to us the most is Minimalism, and when we say Minimalism we think of values like ‘form is content’, but more like the way it exists in Japanese aesthetics and in Bauhaus. Only our ‘stories’ are a little less laconic than the story of a drop on a persimmon leaf in a Haiku. There are forms whose emanation from function does not serve our ambition. No one can convince us that the embroidered stars or the hump on one of our armchair are ‘extravagant ornaments’. It is true that our insistence on them may make production more expensive, but psychoanalysis with a specialist is more expensive than going to a novice psychologist. Our need to express ourselves is sensual, literary or erotic language cannot testify to intellectual infirmity, just a lack of ornament poetics does not necessarily attest to intellectual vigor”.

Naomi Aviv, December 1995, Tel Aviv