What is it with the automata these days? Those relics of a technological era we left behind more than a hundred years ago, aren’t they obsolete? It is true the story of artificial beings is old: it charts the influence of technology across human history. But the meme of mechanical beings didn’t catch on until the principle of Philosophia ancilla theologiae (Philosophy is a slave of Theology) was superseded and philosophers assumed their role as interpreters of the most wonderful miracles of technology.

From the recipes for growing “rational beings” inside cow’s wombs to the animated statues of the Persian alchemist Jâbir ibn Hâyyan, artificial creatures had been linked to the supernatural. In the Iliad, Hephaestus, God of Metals, produces mechanical beings, female servants made out of gold, to help at the workshop. But he produces Pandora out of earth, a creature endowed by the Immortals with the feminine traits of beauty and seduction to be the curse of man, unleashing all the Evils into the world from her infamous box.

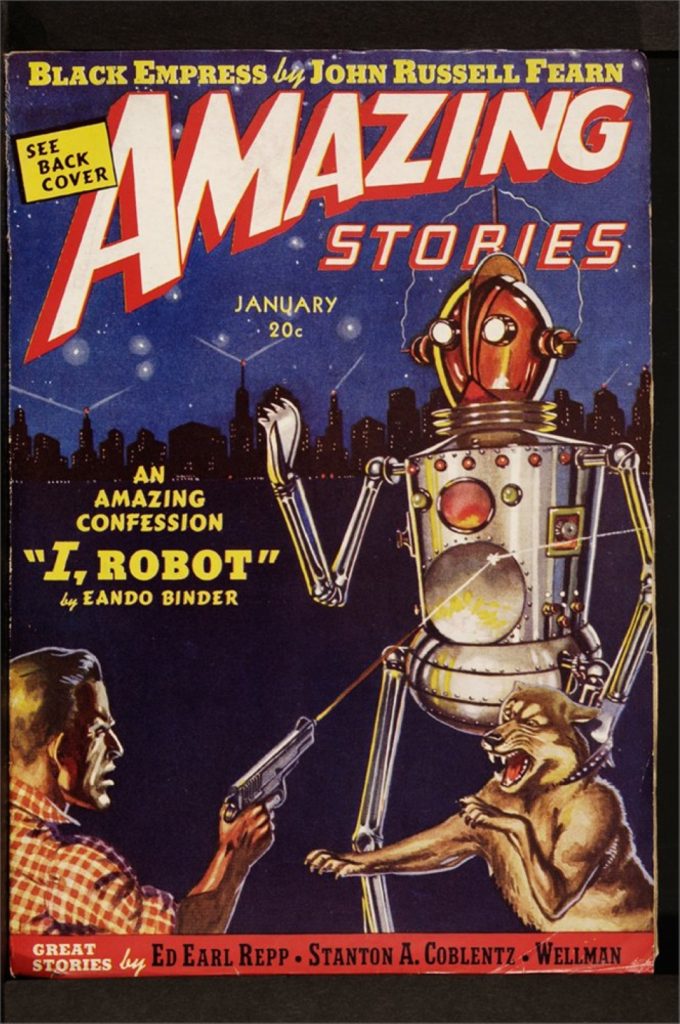

During the Middle Ages, mystics studied the Book of Creation, Sefer Yetzirah, to find the spell of mystical ecstasy that sets a golem in motion, a mud-made ancestor of Frankenstein whose most famous specimen is said to have served the Rabbi Löw of 16th-century Prague (Interestingly, the Czech word for Golem is roboto, which means literally “work” but as related to serfdom. Karel ?apek would refashion the concept, with its troubled connection between artificial beings and slavery, in his Rossum’s Universal Robots (1920), and it was quickly adopted by the international world of science fiction. The derivate robotics, as a discipline of study, was coined later by Isaac Asimov). In 1572, Paracelsus compelled his readers to not “by any means forget the generation of homunculi”, following a recipe that includes putrefying semen and horse manure, reimplemented later with the magic root of mandrake. But when the complex devices started coming out of workshops and Newton published his laws of motion, God dropped the magic and became a clockmaker. This is an image we’ve never managed to shake off.

Isaac Newton -completing a forbidden revolution initiated by Copernicus and bravely implemented by Giordano Bruno and Francis Bacon- proposed a suggestive image of the Universe as a beautiful mechanism ruled by rational forces. When Albrecth von Haller revealed that muscles contract in involuntary response to electrical stimuli, an action independent of will, men also were turned into clocks.

“The human body is a machine which winds its own springs”, wrote Julien Offray De La Mettrie in 1747 in his treatise L’Homme Machine. For this philosopher, Mother Nature was rational and therefore intelligible and predictable, from which he could derive that human beings were too. The general agreement was that, while the complexities of our constitution would render its mechanical reproduction near impossible, engineers would eventually succeed. And that is the unbeaten path taken by the famous automata maker Jacques de Vaucanson when he built his flute playing faun. On the talking automata, offered La Mettrie, “we cannot longer consider it an impossible feat, specially on the hands of the modern Prometeus”.

In those golden days of automata, when science seemed to replace Religion as the “opium of the people”, most of the works were models engineered to increase appreciation of the natural sciences. Their goal was to reproduce the vital functions of the living body, such as circulation of the blood or the respiratory apparatus, in the spirit of “living anatomies”. Despite this premise, the automatiers did not try to produce models of perplexing complexity, so much as an artificial approach to the original process.

Unlike Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca (2000), where we can see the long process of food becoming waste through a network of transparent tubes, their technical entrails were generally hidden to maintain an aura of illusion. This was also because those feats of science were mostly funded by members of the high society, and they were meant to provide for entertainment in their fashionable salons. Among these was Vaucanson’s celebrated mechanical duck. Produced in 1739, it was supposed to digest food “as in real Animals, by Dissolution”. His maker presented a self-explanatory drawing in the Academy and toured with the bird whose repertoire also supposedly included “drinking and playing in the Water with his Bill, and making a gurgling Noise like a real living Duck”.

Back in 1755, the duck was already accused of being “nothing more than a coffee-grinder”, but it made its point; showing that digestion was a chemical and not a mechanical process, like some physiologists defended. Being a fraud didn’t refrain the Duck from being right about digestion. The same fiddle lies at the foundation of the most notorious automata of all times, Wolfgang von Kempelen’s chess player. Also known as the Turk, it managed to win against any adversary, though it was steered by disgraced chess masters hidden in his dark belly.

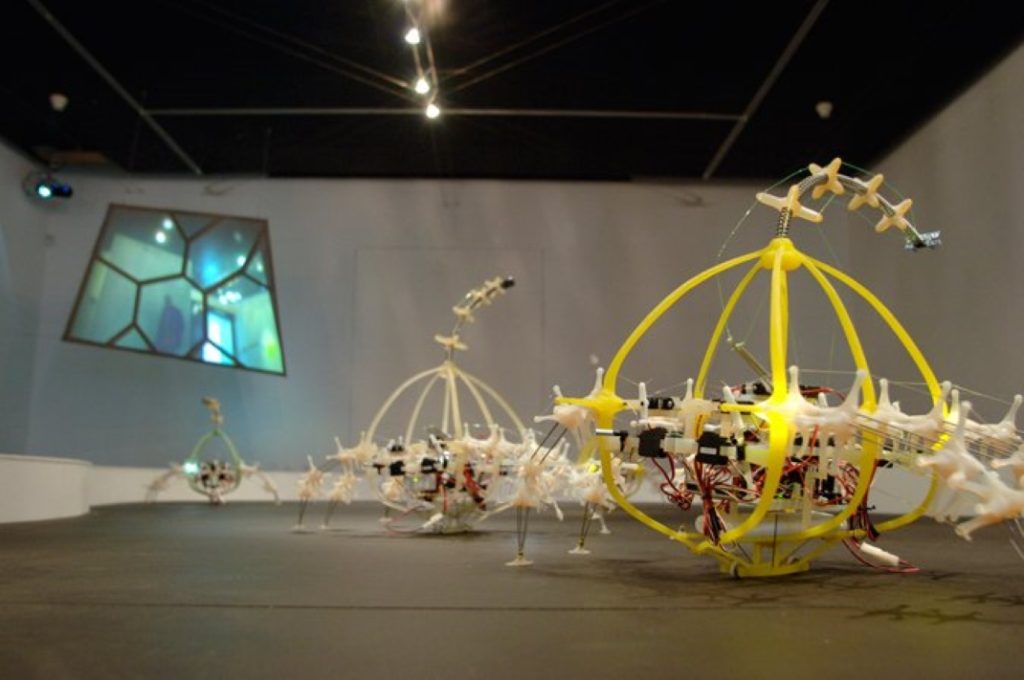

In robotics, biology remains a strong inspiration. There are turtles (Grey Walter’s Elmer and Elsie, 1948), spiders (The Autotelematic Spider Bots, Ken Rinaldo 2006), rats (SCRATCHbot, 2006-2009), fish (Robofish, University of Washington) and Festo’s SmartBirds, a field changing bots apparently capable of fooling other birds. But really it’s mostly about insects. The Laboratory of Intelligent Systems, directed by Prof. Dario Floreano in Lausanne, develops vision-based robots capable of flying indoors without human intervention. They operate either as individual units or as a swarm. On a darker note, the American Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has produced a vast number of robotic insect-based drones serving as weapons or spies for military purposes. They are probably the smallest, yet deadliest automata in history.

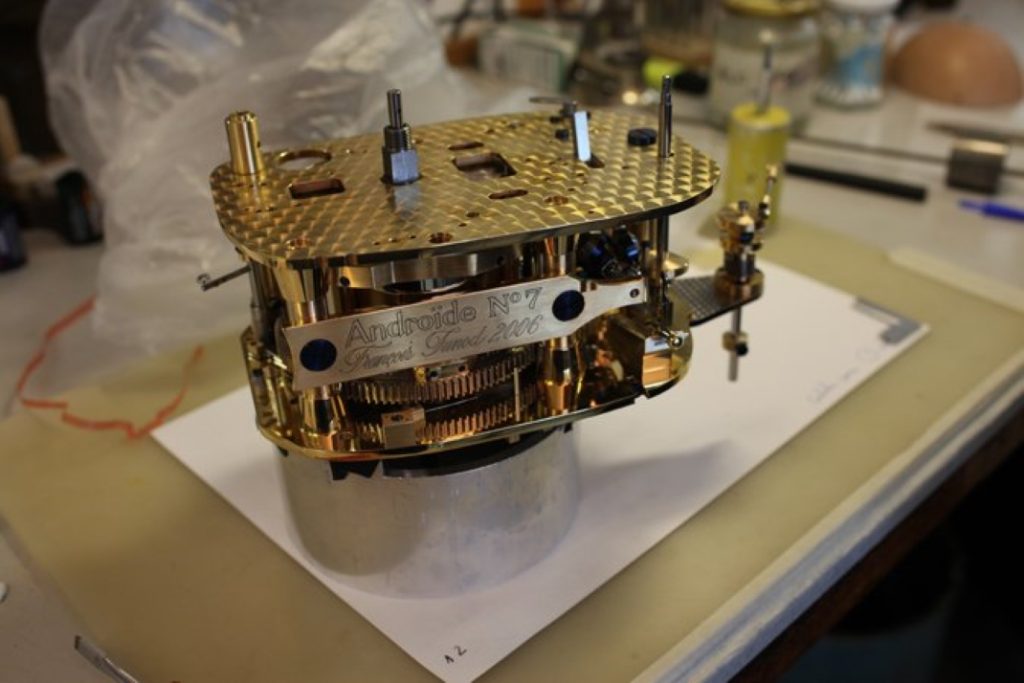

Apart from life-like, the plausibility of automata being “kind of alive” has been frequently reinforced by their ability to execute delicate gestures. We are talking of course about those we consider most human, such as writing or painting; the result of artistic impulses no machine is capable of, its nature being limited by a life of mechanical repetition. This was the path of Pierre and Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, who produced a vast array of wonderful androids (as they called their creations) in the decade of 1770.

The Jaquet-Droz family used organic materials like leather, cork and papier-mâché to give their machines the required softness. They also recruited the village surgeon to aid with their skeletal structures for their divine things. Three of them can still be admired at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. There are two barefoot little boys, fashioned in the Rousseauian model of children’s natural virtues, and one older girl who plays the clavichord. Apart from his pristine calligraphy, L’Ecrivain is even capable of projecting a reflexive irony on the human condition. Among the many sentences he is capable of writing lies a Cartesian classic of anthropomorphic egotism: “I think, therefore I am”. Does he?

This mise en abyme has a disquieting effect on the unaware visitor. Though one could very well say that automata can only resemble life, it is precisely this Cartesian dualism -if he doesn’t think, does he not exist?- that might contain the confirmation or the refutation of our uniqueness. And precisely because automata are nothing but an appearance of reality, they have the power of conveying an image that is somehow stronger than the Real: they have the power to effectively incarnate each and any of our desires. If “man has made man in His own image”, as the astute father or Cybernetics Norbert Wiener pointed out in God and Golem, Inc. (1964), man has been especially willing to apply his fantasies to the opposite sex. It is no surprise that one of the first artificial creatures mentioned in the old books is Galatea, the life-like statue created by Pygmalion.

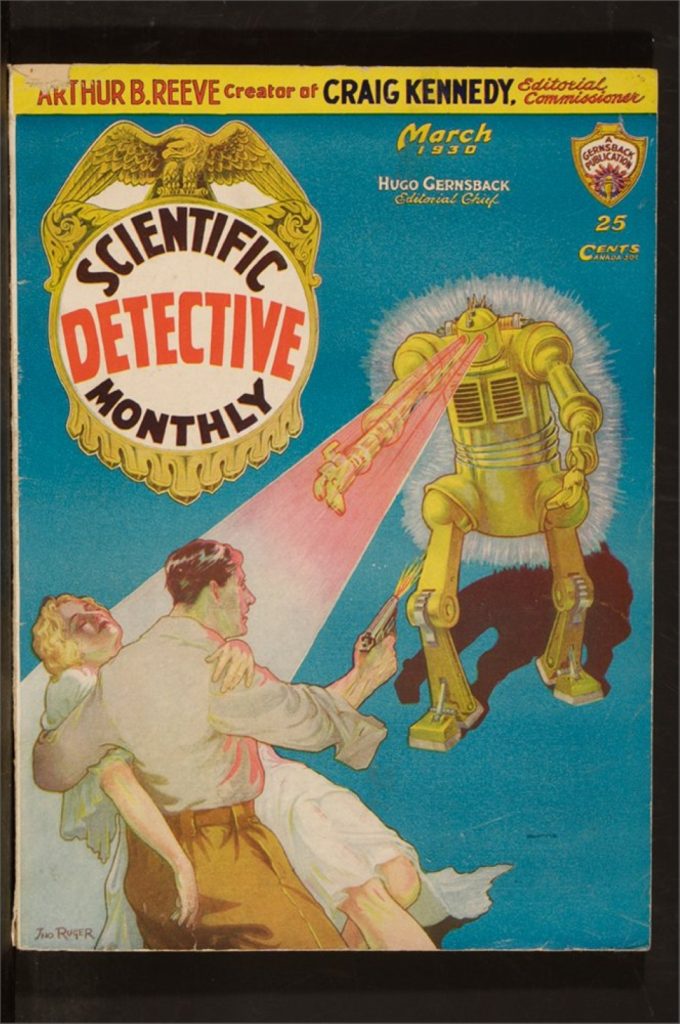

In the great world of science fiction, a genre productively invaded by androids since the first complex anthropomorphic machines walked out of the clockmaker’s workshop, Galatea is both the Witch and the Queen. In The Sandman (1816), E.T.A. Hoffmann sets in motion a typical mad doctor’s routine: the doll Olympia is so human-like that the protagonist Nathanael is totally enraptured by her, despite her fixed gaze and creepy manners. In Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s The Future Eve (1886), the main character (despairing to the point of suicide for the love of a beautiful but stupid young actress) believes he has found the solution in an artificial replica of his brainless fiancée, even though he took an active role in the making of his mechanical bride.

The effigy embodies our desire -the copy being perfectly obedient in its non-judgmental indifference- better than the original is meant to represent. Fashion models are also called mannequins, and they awake the same consuming passions as the inflatable protagonist of Luis García Berlanga’s Grandeur nature (1974). But in the mechanical kingdom, men’s troubled relationship with the gynoid is coupled by a different kind of commotion, a shock that emerges from the mesmerizing features of a creature that is, at the same time, perfectly similar to us and intrinsically opposite. According to Joris-Kark Huysmans, Villier’s best friend, it is only the sad mechanical condition of our own reproductive habits that explains our fascination with those artificial girlfriends. Their incarnation today seems to lay somewhere between the hyperrealistic japanese sexbots and the Girlfriend 2.0. Like Olympia, True Companion’s Roxxxy “can carry on a discussion and expresses her love to you and be your loving friend”. Be careful, Villiers would say: Brunettes are full of electricity.

Whether we are trying to get a date or replace a loved one, humans have been our favorite models for replicating life. It is from this insistence that the automata maker claims the place of God, and the making of automata becomes a blasphemous act. That is to say, hopeless from the start, doomed to fail and prone to capital punishment. As the story goes, Nathanael goes mad, the Future Eve is lost at sea and Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus cannot help but have his masterpiece annihilated by the angry mob. Literature has always showed great concern about scientists’ unholy pretension to dominate the secrets of life.

The Mechanical Luddites

And so it follows, the nineteenth century had a bad thought, one that found its unlikely source in the young Mary Shelley: artificial beings will become uncontrollable in the moment they attain the ability to think. Even worse: they can -and will- become a real menace when they start hunting in packs. When Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was published in 1818, machines had been simplified, standardized and multiplied by the hundreds. As a matter of fact, the mastery of the automata makers has deteriorated as these mechanical creatures became increasingly useful. Vaucanson was, after all, the source of the first completely automated loom.

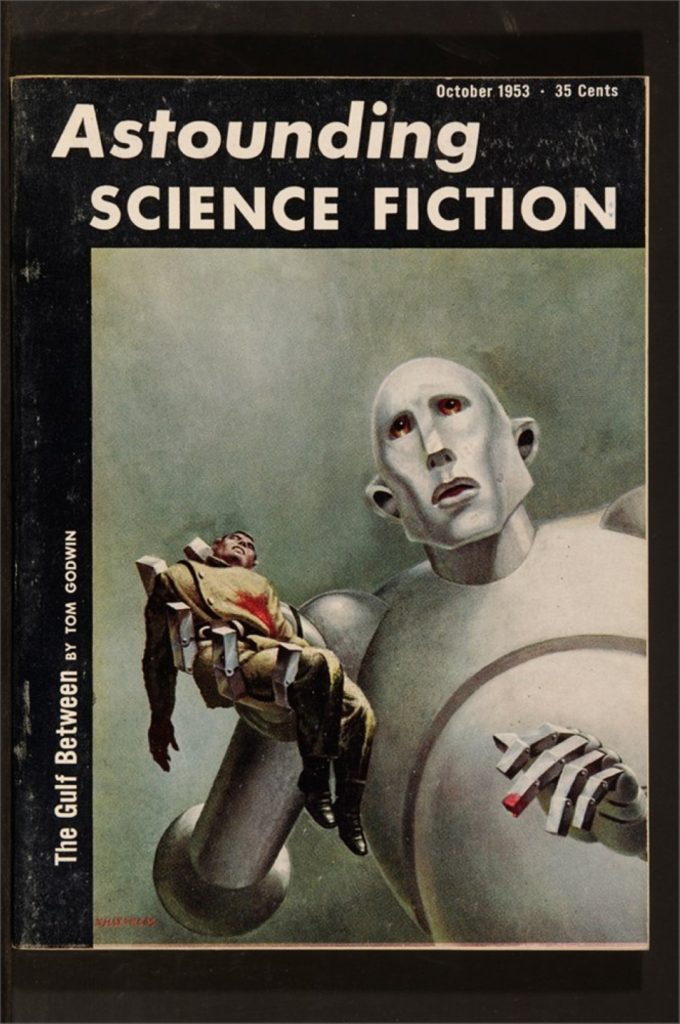

By the time Karel ?apek unleashed his robots in 1921, the uprising of the artificial race that grows sick of slavery and attempts to destroy its maker was already a common place. Modern science fiction would exploit this mercilessly until the prodigal children were rescued by a 22 years Jewish Russian immigrant who taught biochemistry at Boston University. Isaac Asimov, an outsider in every way, studied those creatures that grow murderously jealous of the human condition and found a Freudian source for them: guilt. In our collective imagination, Robots were servants whose improved intelligence hadn’t been met with equal civil rights. They helped us conquer the stars or explore inhospitable planets, and tended to our elders in homes and hospitals, yet we still treated them like toasters. If they were to “wake up” one day, they would totally hate us. With his three laws of robotics, Asimov introduced the idea of an artificial conscience and maybe paradoxically programmed the first real ethics of the machine race. All the while he was pointing out what should have been so obvious; machines will do what they are programmed to do. Even when they became evil, they are just mimicking us.

More interestingly, from the integration of natural and mechanical kingdoms derived, alongside the humanization of the mechanical, the very inverse phenomena. Engineers believed that, when built in great quantity, machines could be the key to an improved society and, importantly, better conditions for the working-class. Unfortunately -as we are rediscovering in this age of hyperconnectivity- it is in their nature to impose their rhythm on those around them, a rhythm whose dehumanizing side-effects Lord Byron described in his defence of the Luddites. They were indefatigable, exchangeable and disposable, so workers became that, too, becoming the cheapest and most disposable piece of the industrial revolution engine. We can say the English frame-breakers were the first robots who rebelled.

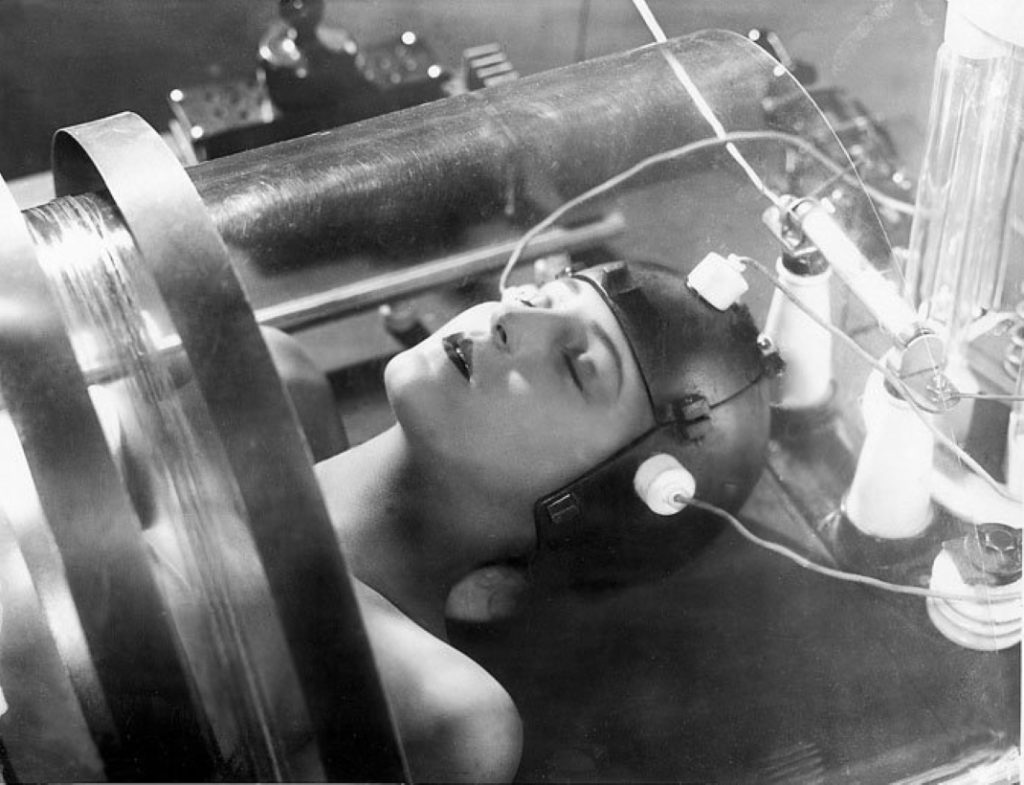

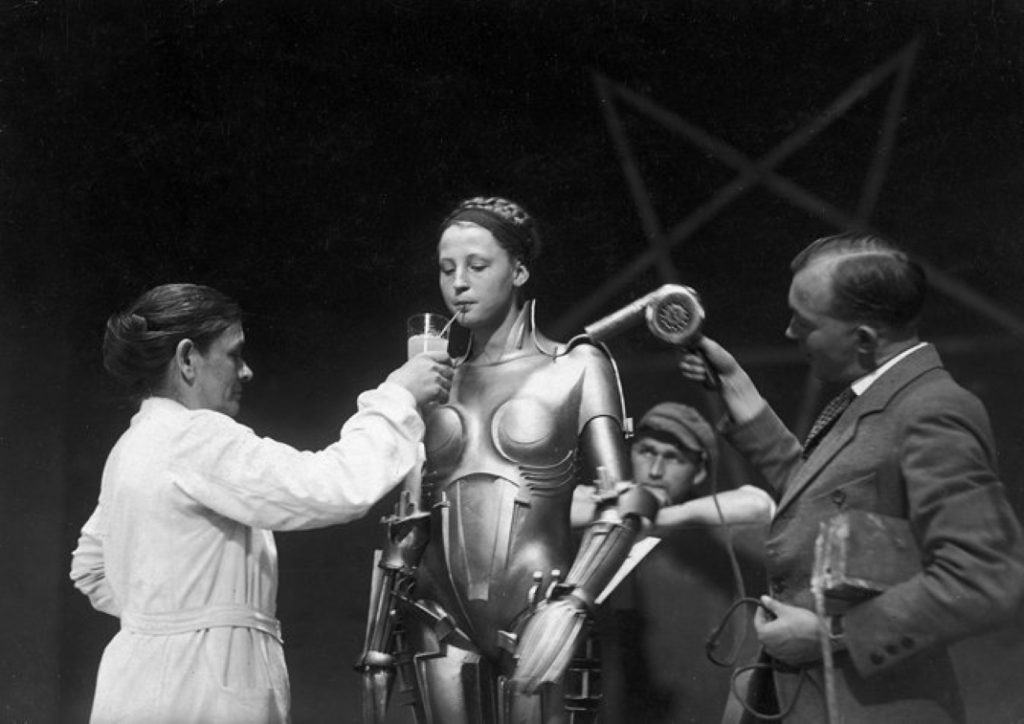

Nowhere is this effect more eloquently seen than in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, where a whole section of the society have become part of a collective organism, announcing the end of the individual. Contemporary science fiction has further explored this disquieting terrain, a ghost that haunted Philip K. Dick more than any other author. As he wrote in 1972, “someday a human being, named perhaps Fred White, may shoot a robot named Pete Something-or-other, which has come out of a General Electrics factory, and to his surprise see it weep and bleed. And the dying robot may shoot back and, to its surprise, see a wisp of grey smoke arise from the electric pump that it supposed was Mr. White’s beating heart. It would be rather a great moment of truth for both of them.” The author of these lines was well aware of the limitations of our creation; in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, replicants can only “live” for four years, not only to allow us to control their destinies, but also to make sure that we are not so alike.

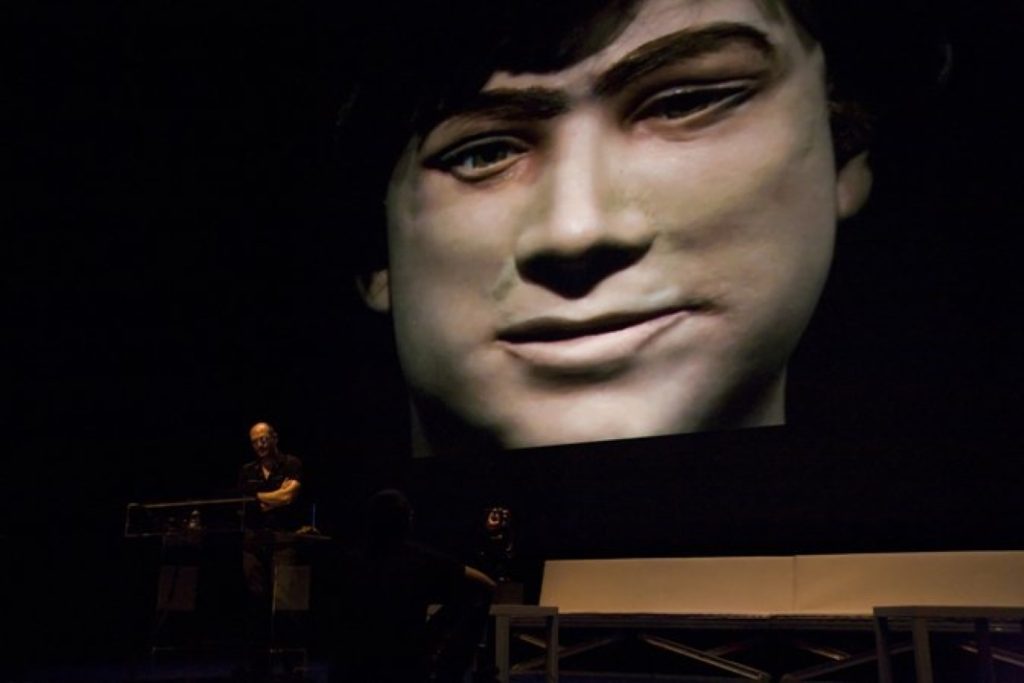

As if to tease him, Hanson Robotics created a robot that not only closely resembles the writer but, as the Neuchâtel writing boy, recites the eeriest passages from the writer’s books. Similarly, Hiroshi Ishiguro created a robot copy of himself Geminoid (2006) and another of his own daughter, named Repliee R1. Consciously or not, it recalls the story of Francine, Descartes little daughter, who died of scarlet fever at a very young age and – according to a legend – was said to be “resuscitated” as a life-size replica doll that travelled with the old man. And who, just like the Huysmans sexy android, ended up in the bottom of the sea.

All about die Unheimlichkeit

When confronting the artificial doppelgänger, an important question arises. If we are so much alike, we must admit we are limited to an empty existential life. If not, then we can say the complexity and inaccessibility of the human condition is reinforced by the very existence of a false reflection. The automata, a mirror of the soul, allows us to identify in ourselves that which is not reproducible or cannot be reduced to simple (or complex) mechanics; that which remains elusive.

Sigmund Freud’s Unheimlichkeit -the uncanny- is the term he employs in his 1919 essay about E.T.A. Hoffman’s The Sand Man to describe the uncertainty and uneasiness we feel around androids and other human-like dolls. The feeling is accompanied by a comforting affectation: the artifice always refers back to that elusive nature of ours. Automata go all the way back to Hephaestus, Pygmalion, Daedalus, Prometheus and also to Narcissus. They remit to the impossibility of defining our essence and can, reversely, confirm our uniqueness: man can thus consider himself the only absolute exception in all Creation, including his own.

However, with the apparition of Artificial Intelligence, the neat distinction between creator and creature is again challenged, as it had been challenged in the past by enlightened thinkers like La Mettrie. In their philosophical works, Gilbert Ryle (The Concept of Mind, 1949) and Arthur Koestler (The Ghost in the Machine, 1967) still refute the Cartesian dualism; “the dogma of the ghost in the machine” -as Ryle refers to it- where a hidden entity called “the mind” lives inside a mechanical platform called “the body”. Can it not be true that, given a certain level of complexity, the mind could end up generating itself in the machine? Nothing allows us to determine where man -that concept we call Man, one not of flesh, bone and blood- begins or ends. And if we were capable of determining its borders, what do we do with the layers of material wrapping? What would we need that frail, putrefying wrapping for?

Both Antonin Artaud and Greg Egan picked up that thread. Artaud exhorts the human race to renounce to his corporealness and get closer to his Maker: “When you will have made him a body without organs, then you will have delivered him from all his automatic reactions and restored him to his true freedom” (To Have Done with the Judgment of God, 1947). And Egan provides the technical implementation with the aid of virtual entities, backups of human minds that eventually detach themselves from their originals and start lobbying for their civil rights (Permutation City, 1994).

Artificial creatures have always been the poster boys for the most advanced technologies of their time: mechanical yesterday, electronic today, info-biological tomorrow. As the result of a human driven process of natural selection -described by Samuel Butler in his visionary essay Darwin among the machines (1863), yesterday’s automata have progressively been substituted by hybrids and other beings of further complexity. The next step in human evolution -states Hanson Robotics- isn’t human.

Funny enough, the Alan Turing Year 2012, will find us like Rick Deckard (the thinly veiled Cartesian character from Blade Runner), falling in love with the replicant who challenges him to take his own test. Relationships between man and creature are so dense and layered that a return to the origins feels not only necessary, but essential. With his analogical simplicity, the automata retains a unique ability to help us delineate the mysteries of our own nature, despite its lack of definitive answers about our own humanity. All armed with metaphorical power, it guides us in our metaphysical quest, ever reminding us that we are just reflecting ourselves on their metallic skin.

****Patrick J. Gyger (b. 1971) is a Swiss historian and writer. From 1999 to 2011, he was the director of “Maison d’Ailleurs” in Switzerland (www.ailleurs.ch), a museum housing one of the world’s largest collections of Science Fiction and Utopia. As such, he has put up more than thirty exhibitions on the main topics or artists of the field and published extensively. One of his recent researchs has resulted in a book on flyings cars in fact and fiction (Haynes, 2011). In October 2008, he opened Espace Jules Verne, a new permanent wing of Maison d’Ailleurs devoted to Extraordinary Journeys. Patrick Gyger has also served as artistic director of the “Utopiales” Festival International in France (www.utopiales.org), from 2001 to 2005. Since January 2011, he is the director of the lieu unique, national center for contemporary arts in Nantes (http://www.lelieuuniqe.com), a leading pluridisciplinary venue for theater, dance, visuals arts, music and literature.

*Translated by Marta Peirano